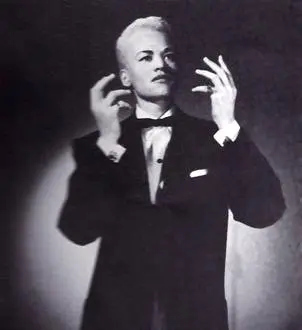

Manhattan Center in 1962 Photo:A Time When Cross Dressing Was A Crime

Throughout the mid-20th century, the LGBTQ+ community in the United States faced significant legal discrimination and harassment. One of the most prominent forms of this harassment came through the enforcement of what was known as the “three-article rule,” an informal policing tactic used to criminalize individuals based on their gender expression.

Though the law itself technically never existed, this tactic and other masquerade laws were applied widely and disproportionately to target LGBTQ+ people, especially those who challenged traditional gender norms.

The Origins of Cross-Dressing Laws

The roots of anti-cross-dressing laws in the United States stretch back to the 19th century. One of the earliest instances can be found in New York’s “masquerade law,” enacted in 1845. Interestingly, this law was not initially intended to target gender expression.

It was designed to punish rural farmers who disguised themselves as Native Americans to resist tax collectors. The law stated that having one’s “face painted, discoloured, covered, or concealed, or otherwise disguised” in public spaces was a crime.

As time went on, however, these laws took on new meanings. By the early 20th century, cross-dressing and gender non-conformity were increasingly viewed as public offences, and the masquerade laws were repurposed to target individuals who presented themselves in ways that deviated from binary gender expectations. During this period, authorities used these laws to arrest people for cross-dressing, a practice that became more common as societal norms around gender were increasingly rigid.

The Informal “Three-Article Rule”

One of the most infamous methods of targeting LGBTQ+ individuals during the mid-20th century was the so-called “three-article rule.” This informal practice required people to wear at least three pieces of clothing associated with their gender assigned at birth to avoid arrest. Failure to do so could result in being detained for cross-dressing, a crime punishable under various masquerade laws.

While the three-article rule was not codified in any formal legal document, its impact was widespread. Stories of people being arrested for violating this unwritten rule surfaced across the United States, particularly in major cities like New York.

The rule was cited in memoirs and interviews from LGBTQ+ individuals recounting their experiences in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. Rusty Brown, a drag king in New York, recalled in a 1983 interview that she had been arrested numerous times for wearing traditionally masculine clothing. She said, “You had to have three pieces of female attire” to avoid being detained for cross-dressing.

Masquerade Laws: A Tool for Harassment

in a ball gown, circa 1940.source:A Time When Cross Dressing Was A Crime

Although the three-article rule was informal, it existed within broader masquerade laws, which were still in effect in several states. These laws allowed the police to arrest people for cross-dressing, often with vague justifications. For instance, in a case in Brooklyn in 1913, a transgender man was arrested for “masquerading in men’s clothes” after being caught smoking and drinking in a bar.

Although the magistrate initially dismissed the case, citing that the masquerade law only applied to those in costume to commit a crime, the police re-arrested the man on different charges, demonstrating how law enforcement could manipulate the legal system to target marginalized individuals.

By the mid-20th century, fear and anxiety surrounding LGBTQ+ people were growing. The public’s increasing discomfort with gender non-conformity and same-sex relationships fueled police crackdowns. Masquerade laws, which had initially been designed for entirely different purposes, were repurposed as tools to harass and arrest LGBTQ+ individuals, even if they weren’t explicitly engaging in any criminal activity.

Bar Raids and Police Intimidation

Applying the three-article rule and masquerade laws was particularly prevalent in LGBTQ+ spaces, such as bars and nightclubs. During this era, police frequently conducted raids on venues where LGBTQ+ people gathered, arresting patrons under charges of cross-dressing. These raids were often brutal, and the consequences for those arrested could be life-altering.

According to Christopher Adam Mitchell, a researcher at Hunter College in New York City, bar raids were common in the mid-20th century, and they specifically targeted gay men and transgender women. Police officers used the three-article rule as an excuse to inspect patrons’ clothing and even subjected them to humiliating body searches to verify their gender identity.

This type of police behaviour blurred the lines between law enforcement and street-level harassment, as it often resulted in sexual assault and other forms of degradation. LGBTQ+ individuals, particularly those who didn’t conform to traditional gender roles, were frequently victimized by police during these raids.

Lesbians and transgender men, however, faced a different kind of intimidation. Rather than being arrested in bar raids, many were accosted by the police on the streets. Rusty Brown’s story of being arrested for wearing pants and a shirt illustrates how walking down the street in non-conforming clothing could lead to arrest.

The Role of Violence and Street Harassment

Police harassment wasn’t the only form of danger faced by gender non-conforming people in the mid-20th century. Street violence was also a constant threat, particularly for individuals who challenged gender norms through their dress. Martin Boyce, a New York City resident, recalled an encounter with a police officer on Halloween in 1968.

Dressed as Oscar Wilde in a costume deemed “too feminine,” Boyce was initially detained by a police officer. The situation escalated when a nearby gang took interest in the altercation. The officer, rather than ensuring Boyce’s safety, turned to the gang and said, “He’s all yours,” effectively encouraging further harassment. Fortunately, Boyce’s bold attitude amused the gang, and they allowed him to pass unharmed.

The convergence of police harassment, legal discrimination, and street violence created a hostile environment for LGBTQ+ people, especially those who did not conform to traditional gender roles. For many, dressing in drag or expressing their true gender identity came with the risk of arrest, humiliation, or physical harm.

The Stonewall Riots: A Turning Point

The Stonewall Riots began in June 1969 at the Stonewall Inn in New York City and are widely regarded as a pivotal moment in the LGBTQ+ rights movement. The riots were sparked by yet another police raid on an LGBTQ+ establishment, but this time, the patrons fought back. Over several days, LGBTQ+ individuals clashed with police in an unprecedented display of resistance against the systemic harassment and discrimination they had endured for decades.

In the wake of the Stonewall Riots, there was a significant shift in public consciousness and LGBTQ+ activism. Arrests for cross-dressing began to decline, although they did not disappear entirely. The informal three-article rule, which had been a vital tool in the police’s efforts to suppress gender non-conformity, also started to fade from use. The riots marked a new era of LGBTQ+ activism, with increased demands for legal protections and greater social visibility.

The moment grew tense as Stormé DeLarverie, standing tall and undeterred, found herself in a heated confrontation with law enforcement officers outside the Stonewall Inn on a warm June night in 1969. DeLarverie, a masculine lesbian with a strong sense of justice, was not just any bystander. Born in New Orleans in 1920 to a black mother and a white father, she had carved out a space for herself as an entertainer and civil rights icon, performing at prestigious venues like the Apollo Theater and Radio City Music Hall. Beyond her stage presence, Stormé was a fierce community protector, often serving as a bouncer, bodyguard, and the so-called “guardian of lesbians in the Village.”

On that pivotal night, as the police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in Greenwich Village, Stormé’s confrontation with the officers became the spark that lit the fuse of rebellion. Witnesses and DeLarverie herself would recount how her refusal to be silently carted away and her struggle against the police inspired the crowd. People who had long endured harassment and discrimination saw a call to action in her defiance.

Despite the progress made after the Stonewall, masquerade laws disappeared after some time. New York’s masquerade law, initially passed in 1845, remained on the books long after the Stonewall Riots. In 2011, the law was even used to arrest protestors during the Occupy Wall Street movement, showing that these outdated laws could still be applied in new contexts.

Nevertheless, the enforcement of these laws against the LGBTQ+ community diminished significantly after Stonewall. Public sentiment had shifted, and the LGBTQ+ rights movement had gained momentum. In 2019, on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, the New York City Police Department issued a formal apology for its actions during the raid, acknowledging the harm caused to the LGBTQ+ community.