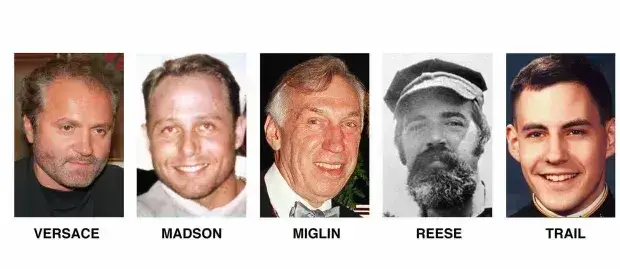

On the morning of July 15, 1997, Gianni Versace, the mythical Italian fashion designer, began his day in a way familiar to many who knew him well. He was up early, making calls to Milan and doing some work before strolling out of his opulent South Beach mansion, Casa Casuarina, and heading to his regular haunt, the News Café. Situated just three blocks from his home on the bustling Ocean Drive, it was here that Versace would stop for coffee, greet familiar faces, and pick up the latest issues of Vogue and The New Yorker.

It seemed like a typical day in the glamorous world of Versace, but it was to be his last.

As Versace returned to Casa Casuarina, walking up the grand marble steps to unlock the iron gate, his world came to a sudden and violent end. Out of nowhere, a man wearing casual clothes, a tank top, shorts, and a baseball cap approached him. That man was Andrew Cunanan, a 27-year-old on the run, already wanted for four brutal murders in three different states.

Without a word, Cunanan pulled out a gun and shot Versace twice, execution-style. The gunshots rang through the muggy streets of South Beach, silencing the world of fashion’s brightest star. As quickly as the violence had erupted, Cunanan calmly walked away, disappearing into the chaos that was now South Beach.

Cunanan’s arrival in Miami two months earlier had gone unnoticed. The manhunt for him was already nationwide, his face plastered on FBI Most Wanted lists. But despite his violent spree and notoriety, Cunanan had managed to live in plain sight, slipping through the cracks of law enforcement in a city filled with tourists, celebrities, and the gay nightlife scene where he felt invisible.

As news of the fashion designer’s death spread, his siblings, Donatella and Santo, hurried to Miami to claim his body. A week later, on July 22, 1997, Versace was given a funeral fit for royalty at Milan’s grand Duomo Cathedral. Attended by fashion stars like Anna Wintour, Karl Lagerfeld, and his muse Naomi Campbell, the service was a sad goodbye to a man who had shaped fashion and created the supermodel phenomenon. Elton John and Sting sang “The Lord is My Shepherd” rendition through the cathedral’s cavernous halls.

Back in Miami, the hunt for Cunanan reached a fever pitch. Less than two weeks after Versace’s death, on July 23, 1997, Cunanan was found dead on a houseboat not far from where he had killed Versace. He had taken his own life with the same gun used in his murderous spree. His death marked the end of the search, but it also left behind a trail of unanswered questions.

Who was Andrew Cunanan?

Andrew Cunanan’s story is as much about his troubled upbringing as it is about the final three months of his life, during which he murdered five people, including fashion designer Gianni Versace.

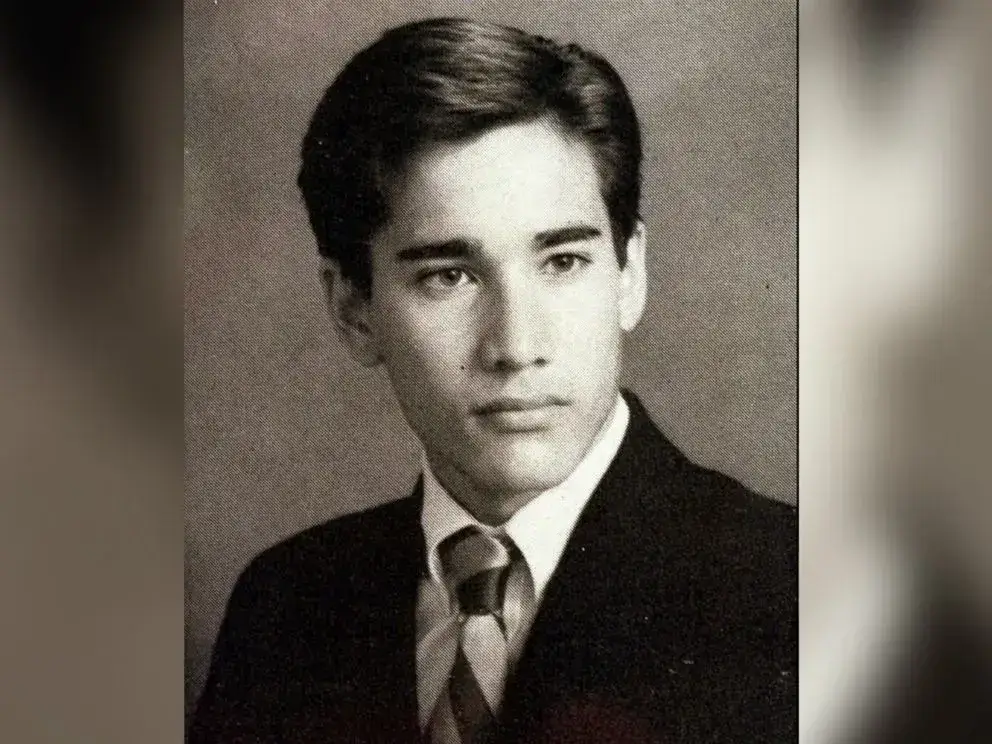

Cunanan’s life began in a seemingly ordinary way. Born in National City, California, on August 31, 1969, he was the youngest of four children. His father, Modesto Cunanan, was a Filipino-American who served in the U.S. Navy and later worked as a stockbroker. At the same time, his mother, Mary Anne Schillaci, was an Italian-American homemaker. However, Cunanan’s early life showed signs of trouble beneath this mask of simplicity. His father, after facing legal problems, fled to the Philippines to avoid arrest, leaving the family behind. Andrew, who had once been the centre of attention at his prestigious private school, was now dealing with a broken home and financial struggles.

Cunanan’s social behaviour was marked by his ability to manipulate and charm those around him. He often used his wit and intelligence to hide a deep-seated need for approval and control. This tendency only intensified when he began frequenting the gay nightlife in San Francisco and later moved to the Castro District, a vibrant hub of the LGBTQ+ community. However, his opportunistic nature sets Cunanan apart from others in the scene. He developed relationships with wealthy older men, relying on them for financial support while living a hedonistic lifestyle. He also adopted several aliases, using different identities to suit his needs, blending into various social circles across San Diego, San Francisco, and Scottsdale.

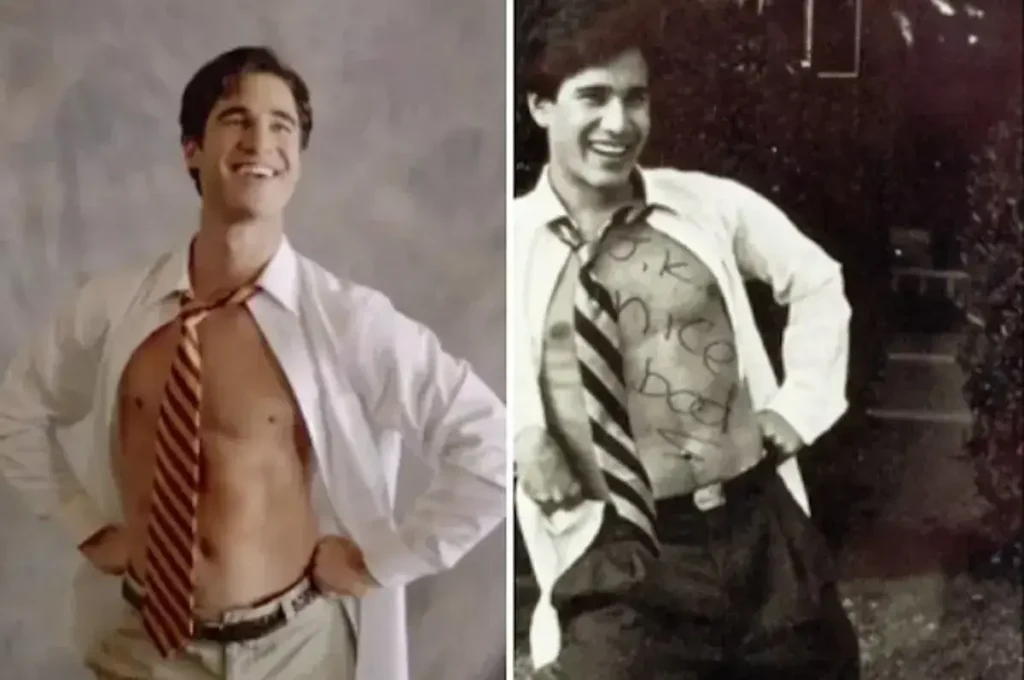

Despite his outward charisma, those closest to Cunanan noticed his increasingly erratic behaviour. Friends became concerned as he began abusing drugs like methamphetamine and prescription opioids. His life spiralled further into chaos when his long-distance relationship with architect David Madson ended in 1996. Cunanan, who referred to Madson as “the love of my life,” was devastated, though Madson sensed something “shady” about him.

His life plunged when Cunanan left San Diego for Minneapolis in April 1997. He was heavily in debt, estranged from many of his close friends, and increasingly paranoid. His trip to Minneapolis, under the guise of “taking care of business,” would mark the beginning of his violent killing spree.

The first victim was Cunanan’s friend Jeffrey Trail, a former naval officer. On April 27, 1997, Cunanan brutally beat Trail to death with a hammer in the apartment of David Madson, his ex-lover. Trail’s body was found rolled up in a rug, and soon after, authorities labelled Madson as either a suspect or a hostage. Cunanan then turned his violence on Madson himself, killing him a few days later and abandoning his body near a lake north of Minneapolis.

Fleeing to Chicago, Cunanan’s third victim was Lee Miglin, a prominent real estate developer. Cunanan’s method of killing Miglin was gruesome, involving torture and mutilation. Miglin’s death puzzled investigators as there was no apparent connection between the two men, and some speculated that Cunanan may have known Miglin through his circle of wealthy connections. However, this theory was never substantiated.

The spree continued when Cunanan murdered William Reese, a cemetery caretaker in New Jersey, to steal his truck. At this point, Cunanan had become one of the FBI’s most wanted fugitives, and his whereabouts were closely tracked as he made his way to Miami.

For two months, Cunanan evaded capture while staying in a Miami Beach hotel under his name. Despite being on the run, he lived relatively openly, going out in public and pawning stolen items. His final act of violence came on July 15, 1997, when he brazenly shot Gianni Versace on the steps of his Miami Beach mansion. The murder of Versace brought the elusive Cunanan into the international spotlight.

Eight days after Versace’s murder, Cunanan’s life ended in a Miami houseboat, where he shot himself with the same gun he had used in his killings. With his death, many questions about his motives and mental state were left unresolved. Authorities speculated that Cunanan’s escalating violence may have been fueled by his failing relationships, drug abuse, and possibly an undiagnosed mental disorder.

Why did Cunanan murder Versace?

Twenty years after the murder of fashion designer Gianni Versace, the motive behind Andrew Cunanan’s actions remains ambiguous. Although Cunanan and Versace did not have a close relationship, reports indicate they may have met briefly before the crime.

Federal investigators suggested that Cunanan’s targets were primarily gay men. At the time of the murder, Versace was in a long-term relationship with Antonio D’Amico. There are indications that Cunanan may have been seeking vengeance against former lovers or clients whom he suspected of having transmitted HIV to him.

What is well-documented is that Versace was not Cunanan’s initial victim; he was a serial killer linked to at least four other homicides. Cunanan had made the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list and was the focus of a nationwide manhunt when he murdered Versace. During this period, he was reportedly hiding out within Miami Beach’s LGBTQ community.

Gianni Versace’s final fashion show

Gianni and Donatella Versace experienced notable friction during the winter and spring of 1996, mainly because Gianni disagreed with Donatella’s choice of advertising campaign. According to Maureen Orth’s book, which serves as the foundation for the FX series, this period was marked by a struggle for power and balance between the siblings as they sought to share the spotlight.

Journalist Ball noted that Gianni’s decision to alter his will in September 1996, leaving his company shares to his niece Allegra instead of his brother or sister, was made secretly and fueled by growing bitterness toward his siblings.

The tension in their relationship was palpable, especially during Gianni’s final fashion show. Fashion expert Smith observed that Donatella felt she was no longer subordinate to her brother but an equal. In creative industries, achieving parity can be challenging; someone ultimately must make the final decisions.

As a result, their collaboration often felt disjointed, with differing styling and model choices that prevented a cohesive vision.

This aesthetic divergence was evident during a specific runway show, prompting American Crime Story costume designer Lou Eyrich to craft looks that reflected their distinct styles. Eyrich explained that Gianni’s designs featured vibrant colours, creams, pinks, yellows, and reds. At the same time, Donatella’s models embodied a more “waif, heroin-chic” aesthetic, favouring black clothing and heavy eye makeup. This visual distinction was critical in illustrating their differing creative philosophies.

Despite the hurdles, Versace’s last fashion show received widespread acclaim. Competing with bold designers like John Galliano and Alexander McQueen, the Associated Press highlighted Gianni’s show, which proclaimed him the “King of the Night.” Fashion director Joan Kaner described the collection as “terrific, sexy, and modern.” At the same time, The New York Times acknowledged the collection’s unevenness, noting that some designs succeeded while others fell flat.

Reflecting on their unresolved issues after Gianni’s death, Smith remarked on the tragedy of their conflicts over seemingly trivial matters like models. In the years since, Donatella has expressed her feelings of loss, stating, “My brother was the king, and my whole world had crashed around me.”

Looking back, the collection feels surprisingly prophetic. It was primarily black, with 53 out of 83 looks featuring this colour. There was also a clear religious theme, highlighted by large jewelled crosses.

Versace mentioned that this was inspired by the Glory of Byzantium exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where these pieces are currently on display as part of Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. Many outfits had an intense monochrome look reminiscent of a nun’s habits but with a sensual twist. At the same time, the models wore their hair pulled back like Renaissance portraits.

Fashion critic Amy Spindler noted in The New York Times that “Mr. Versace pushed himself as hard as the younger designers.” His couture became a testing ground for ideas; for every dress that went too far, there was one that worked beautifully. Versace’s play with shoulder pads, which were making a comeback through 80s styles, aligned well with the times.

Having designed with shoulder pads before, he reworked the idea, exposing them outside dresses and decorating them with crystals or his signature Oroton aluminium mesh. This style has influenced fashion for years and can still be seen today.

Donatella Versace shared that her favourite of Gianni’s collections was his last, inspired by Byzantine themes. However, she didn’t reference it in her Tribute collection because she felt it was too similar to what young designers are doing now.

Gianni Versace’s final collection blended sacred and sensual elements beautifully. The collection featured a dress with the modesty of a nun’s habit perfectly fitting the body and a short wedding gown adorned like an Orthodox icon. This collection captured Versace’s love for decoration and femininity while staying current with changing fashion trends.

This collection poses interesting questions about what direction Gianni Versace’s work would have taken if he had continued to live. Ultimately, these pieces should be displayed in a museum where they have ended up.